*This content has been reviewed by Dr. Donna Vine (Agriculture, Food and Nutritional Sciences, University of Alberta); Last updated February 2024

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a group of disorders affecting the heart and the blood vessels. This includes peripheral vascular disease, atherosclerotic CVD, coronary heart disease, as well as ischemic vascular events such as heart attack and stroke. CVD and ischemic vascular events are a leading cause of death globally and in Canada (1, 2).

- Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease. The development of CVD depends on many risk factors, including those that cannot be modified and those that can be.

- Dietary and Lifestyle Recommendations. Consuming excess Calories from carbohydrates, fat, or other macronutrients, or consuming too much sodium may influence CVD risk factors.

- Sugars and Cardiovascular Disease. Current reviews of the evidence suggest it is the consumption of excess Calories, rather than sugar per se, that influences CVD risk factors.

- Food Sources of Sugars and Cardiovascular Disease. Current evidence suggests an association between sugars-sweetened beverages and hypertension, however other food sources of sugars either show no effect or a protective effect.

Risk Factors for Developing Cardiovascular Disease

The development of CVD depends on some risk factors which cannot be controlled, while others may be modified to delay or prevent CVD development (see table below).

| Unmodifiable Risk Factors for CVD (3) | Modifiable Risk Factors for CVD (4) |

|---|---|

|

|

Maintaining a healthy body weight is encouraged as an important step in promoting cardiovascular health, as many factors leading to weight gain such as lack of exercise and an unhealthy dietary pattern can also contribute to CVD development.

Dietary and Lifestyle Recommendations to Maintain Cardiovascular Health

To maintain cardiovascular health, Heart & Stroke encourages Canadians to eat a healthy and balanced diet, control salt intake and be physically active (5). According to Heart & Stroke, a healthy and balanced diet includes:

- Eating lots of vegetables and fruit

- Choosing whole grain foods more often

- Eating a variety of foods that provide protein

- Eating fewer highly processed foods that are high in added sugars, salt, and fats

- Reducing intake of sugars-sweetened beverages

The 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in the Adult suggest that combining multiple low-risk health behaviours is associated with benefit for the prevention of CVD (6). These include:

- Achieving and maintaining a healthy body weight,

- Consuming a healthy diet,

- Engaging in regular physical activity,

- Smoking cessation,

- Limiting alcohol consumption to no more than moderate, and

- Ensuring sufficient sleep duration.

Sugars and Cardiovascular Disease

A number of international health agencies have reviewed the scientific literature on sugars and CVD. For example,

- European Food Safety Authority - Evidence did not support a relationship between sugars intake and CVD risk. There was low-moderate quality evidence for a relationship between high intakes of added and free sugars and certain CVD risk factors (blood pressure, elevated blood lipids) (7).

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (UK) - There is no association between sugars and coronary artery disease events, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, fasting blood total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol or triglyceride (8). However, the intake of sugars is positively associated with increased energy intake, which reflects the role of sugars in contributing to total dietary energy.

While there are no clinical trials available that have assessed sugars intake with clinical outcomes of CVD (as these require long-term follow-up over many years and most nutrition trials may only be weeks or months, surrogate outcomes and CVD risk factors, such as blood pressure and blood lipids, are used to assess the association.

- A systematic review and meta-analysis (SRMA) of randomized controlled trials found that higher compared with lower intake of sugars was associated with modestly higher blood lipids and diastolic blood pressure (9). There was no association with systolic blood pressure.

- Increased or decreased body weight of participants appeared to be a factor, although results were not consistent.

- A limitation to some of these studies is that most are less than 8 weeks in duration, so longer term outcomes can’t be assessed.

- A SRMA of prospective cohort studies showed an association with CVD mortality for high intakes of total and added sugars, with an observed threshold of >65 g added sugars or 13% of total energy (10).

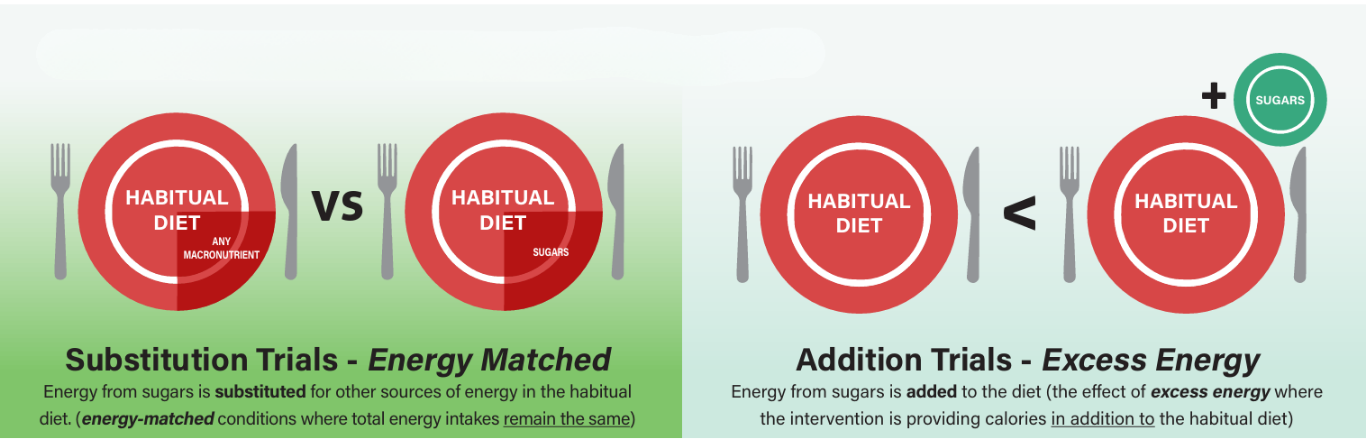

The evidence instead suggests that the effect of sugars on CVD risk is dependent on the amount of excess calories provided by sugars in the diet (11).

- When sugars are substituted for other sources of carbohydrates, providing the same amount of total calories in the diet, there are no effects observed for any markers of CVD risk.

- When sugars are added on top of a regular diet providing additional calories, there is an increase in some aspects of CVD risk such as changes to some blood lipids, but no significant changes to blood pressure.

Food Sources of Sugars and Cardiovascular Disease

Which foods and drinks sugars come from in the diet is important when it comes to heart health. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found an association between sugars-sweetened beverage intake and high blood pressure (12, 13).

However, other food sources of sugars, such as dairy desserts, fruit drinks, and sweet snacks, had no association, and fruits, 100% fruit juice, yogurt and whole grain cereals had a protective effect against high blood pressure (12, 13).

For more information, additional resources include:

Recent news items include:

References:

- The World Health Organization. 2020. The top 10 causes of death [Internet].

- Statistics Canada. 2023. The 10 leading causes of death (2019 to 2022) [Internet].

- Heart and Stroke. 2023. Heart and Stroke Risk and Prevention [Internet].

- Government of Canada. 2023. Prevention of Heart Diseases and Conditions [Internet].

- Heart and Stroke. 2023. Healthy Eating [Internet].

- Pearson GJ, Thanassoulis G, Anderson TJ, Barry AR, Couture P, Dayan N, Francis GA, Genest J, Grégoire J, Grover SA, Gupta M, Hegele RA, La D, Leither LA, Leung AA, Lonn E, Mancini GBJ, Manjoo P, McPherson R, Ngui D, Piché ME, Poirier P, Sievenpiper J, Stone J, Ward R, Wray W. 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in the Adult. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37:1129-50.

- European Food Safety Authority Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens. Scientific Opinion on the Tolerable Upper Intake Level for Dietary Sugars. 2022 p. e07074.

- Public Health England Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. SACN Carbohydrates and Health Report. London, UK: Public Health England; 2015.

- Te Morenga LA, Howatson AJ, Jones RM, Mann J. Dietary sugars and cardiometabolic risk: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of the effects on blood pressure and lipids. AJCN. 2014;100(1):65-79.

- Khan TA, Tayyiba M, Agarwal A, Mejia SB, de Souza RJ, Wolever TMS, Leiter LA, Kendall CWC, Jenkins DJA, Sievenpiper JL. Relation of total sugars, sucrose, fructose, and added sugars with the risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(12):2399-2414.

- Khan TA, Sievenpiper JL. Controversies about sugars: results from systematic reviews and meta-analyses on obesity, cardiometabolic disease and diabetes. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55:25-43.

- Lui Q, Ayoub-Charette S, Khan TA, Au-Yeung F, Mejia SB, de Souza RJ, Wolever TMS, Leiter LA, Kendall CWC, Sievenpiper JL. Important food sources of fructose-containing sugars and incident hypertension: A systematic dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. JAHA. 2019;8:e010977

- Lui Q, Chiavaroli L, Ayoub-Charette S, Ahmed A, Khan TA, Au-Yeung F, Lee D, Cheung A, Zurbau A, Choo VL, Meijia SB, de Souza R, Wolever TMS, Leiter LA, Kendall CWC, Jenkins DJA, Sievenpiper SL. Fructose-containing food sources and blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. PLoS One. 2023;18(8):e0264802